I made a mistake in a concurrent program

I was working on the concurrency part of my main project at work today. The program executed a series of steps in order to accomplish its task. Many of these steps could run in parallel, but some steps could only run after certain other steps.

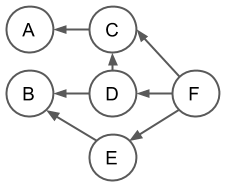

I organized these steps into a dependency graph. Each step defined previous steps it needed to wait on before running. Steps with no dependencies could run immediately. With this structure, many steps could run at the same time, but no step would run before they were supposed to.

Example of an execution dependency graph with steps A…F

Each step would submit itself to an execution manager to either run immediately (no dependencies) or run after some other steps (after its dependencies). Upon submission, this step would receive a future. Other steps would then use this future to retrieve the result of that step after it finishes. I decided to be a bit fancy and lazily initialize these futures, where the step would only submit itself to the execution manager if another step required it to run.

All seemed well. I added a check to make sure that a future is always finished before another step retrieves its result. This makes sure that I defined the dependencies for the steps correctly. This was important because if I did not define the the dependencies correctly, steps might unintentionally block threads from executing useful work. Unintentional blocking would decrease the efficiency of the parallel execution.

After running the tests a few times, the check failed. I must have set up the graph incorrectly somewhere. I must have forgotten to define some dependency… So, I went down a rabbit hole for a few hours, auditing each step to make sure I had all the necessary dependencies set. But, every so often, the check still failed.

I thought for a long time. And then it suddenly hit me. I figured it out. This whole time I had set up the dependency graph correctly. The problem lied not in my dependency graph, but rather in my lazy initialization.

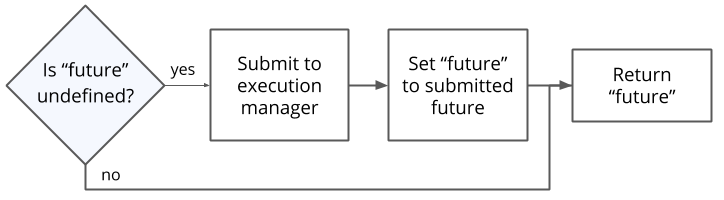

The lazy initialization worked like this. Each step has a “future” variable and a “get future” method. The “future” variable is initially undefined. When another step calls the “get future” method the first time, the method submits the step to the execution manager and sets the “future” variable. Further calls to “get future” returns that submitted future.

“get future” method

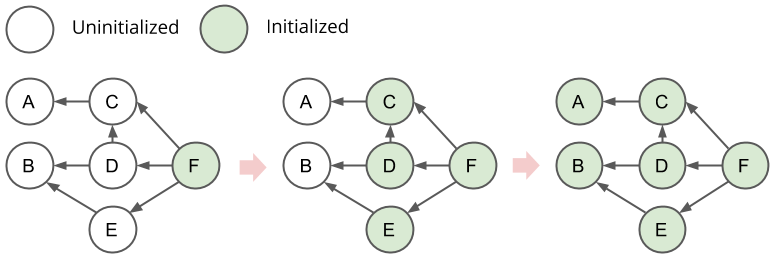

Each step calls its dependencies’ “get future” method to get the futures to wait upon. Therefore, this initialization design builds the dependency graph from the last step backwards.

Illustration of how the dependency graph is built backwards

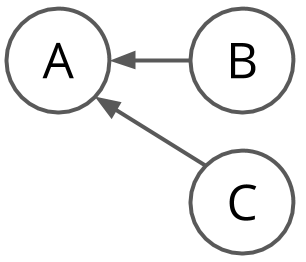

From this, I noticed the flaw in this initialization method - it had a blaring race condition. For example, let’s take a look at a scenario where two steps depend on a single step:

Let’s say B and C happened to call A’s “get future” method at the same time. B’s call has A submit future 1 to the execution manager. C’s call has A submit future 2 to the execution manager. This causes A to set its “future” variable to future 1 and then change it to future 2. Later, B calls A’s “get future” method again. B receives future 2, and not future 1 as it had expected.

So, how do we solve this problem? By not doing this backwards initialization. Each step should just initialize itself. Each step would submit itself to the execution manager upon creation. This means that each step would only ever create one future. Each step’s “get future” method would always return the same future.

I made this fix, and the problem disappeared.

In essence, the real issue is that I had mutable state. All concurrent objects should be immutable. I ran into this problem here because I had concurrent objects (the steps) be able to mutate state (set a “future” variable). By setting the “future” variable upon construction of each step, I made each step immutable and therefore immune to any parallel execution problems.

So, yeah, make sure all your concurrent objects are immutable. And don’t try to do fancy stuff before thinking it through completely.

Remarks

This problem wouldn’t exist with the original initialization method had the dependency graph been a tree. This is because in a tree, each node has only one parent, and therefore each “get future” method could only be called at most one time. But, our dependency graph is a directed acyclic graph and, in practice, many nodes have several parents.

Comments