The 25 Horses Problem

I recently came across a video titled HARD Google Interview Question - The 25 Horses Puzzle. I don’t think Google asks any brain teaser problems so I decided to check it out. Although the problem was formulated like a brain teaser, I found it to actually be a very well-designed technical problem. I could actually apply various technical problem-solving techniques to solve this problem - although it involved no coding. The problem describes a scenario with a “real-world” setting, but it could be modeled nicely with graph theory and topological ordering. The video presented a nice intuitive explanation of the solution, but I want to show how certain techniques can be used to approach this problem step-by-step - techniques that could be applied to problems of all sorts.

So, the problem goes as such:

You want to find the fastest 3 horses in a group of 25 horses. You can only race 5 horses at a time. You don’t have a stopwatch, so you can only know the ranking of each horse within each race. How many races do you need?

I enjoyed this problem since it wasn’t one of those brain teasers where there’s some trick to solving it that wasn’t presented in the original problem. The solution didn’t involve adding elements of manipulation to the scenario (like you give steroids to horses to make them faster). There wasn’t some wisecrack answer like “just one race if we are lucky!”. The solution formulates itself completely within the scope of the problem. In fact, the problem could be reduced into a raw representation such that it could be modeled in a mathematical format.

To re-formulate the problem in a technical sense:

- There are 25 elements that have some ordering from fastest to slowest among them (a strict ordering).

- You can perform some computation called race that can give the relative ordering of any 5 of those elements. How many times do you need to run race in order to find the first 3 elements in the ordering?

The intent of the problem isn’t for us to give a number of races needed, but rather to provide a proof as to the number of races. This proof is like one of those classic two-sided proofs where the goal is to prove an equality. In these proofs, to prove that the solution is exactly some value, you prove that the solution is at least that value and also at most that value - and therefore the solution must be exactly that value. However, in this case, the two proofs are 1) that a solution exists for some value and 2) that the solution must be at least that value - therefore, that value is the minimum possible value.

So, for this problem, I needed to prove that:

- I can find a small number of races that works, and that

- The minimum number of races needed is that number

I started with a naive answer to prove the first lemma (there exists some number of races that works). Since there are 25 horses, if I race every pair of horses, I can rank each of the horses in their exact order. Therefore if I race the 25 horses 25 times each, I have the exact ordering - this is 252 races. Then, I realize that there are a lot of duplicate races. Eliminating these duplicate races I find the actual number of pairings:

- The first horse has 24 other horses to pair.

- The second horse has 23 other horses to pair. The pairing for the first horse is already covered.

- The third horse has 22 other horses to pair…

…

24. The 24th horse has 1 other horse to pair.

25. The 25th horse has no other horses to pair.

This linear summation can be easily expressed as , or 300. That’s quite a few races still.

So, then I tried to look for what other races I could eliminate (don’t take this out of context) - which ones did not need to happen - what inefficiencies my algorithm had. The two main inefficiencies were that:

- I was not utilizing the full potential of the race function. I am discarding useful results by just looking at the ordering for the first two of each race result, and that

- I am finding the full ordering of all 25 horses, whereas I only need the ordering for the first 3.

One technique I like to use is to represent the problem in a model I have worked with extensively before - one that I am familiar with and have solved other problems in. Doing so would helps me to apply techniques I’ve learned from working with that model. In this problem, we are trying to find the (ordering) relationship between pairs of horses. What better model to represent this than a graph.

For those unfamiliar with graphs in discrete math, a graph is just a bunch of nodes and edges that connect them. In other words, it is the colloquial equivalent of a network (like a social network, or a network of highways).

An example of a graph

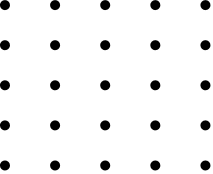

In our case, the nodes are the horses, and each edge represents a pair of horses. We can have our graph be a “knowledge” graph. We start with 25 nodes with no edges. Then, every edge we add between two horses represents knowledge of the ordering between the two horses - knowledge of which horse is faster. That means that each race could add new edges to our graph.

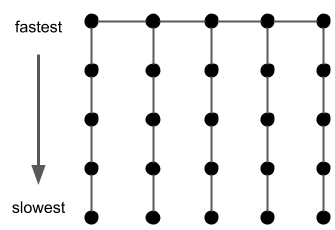

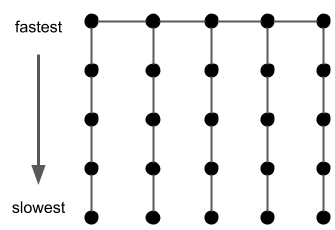

A 25-node graph with no edges

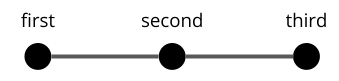

With this model, the original approach of running 300 races is equivalent to adding an edge between every node. In fact, there are exactly 300 edges if we were to connect all the nodes with edges (see complete graph). Many of these edges are not necessary. In fact, we only need two edges to know the fastest 3 horses - the edge between the fastest and second fastest, and the edge between the second fastest and third fastest.

We win if we find these edges

However, this does not mean that we only need one race. We could get lucky and have our top 3 horses be in the one race we hold, but the problem is asking for a solution that could work in all cases.

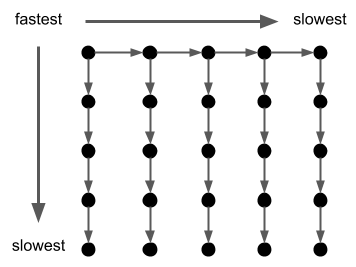

Now, it made sense to start building the solution from the bottom up and tackle the second lemma (the number of races needed is at least some number). The initial graph is 25 nodes with no edges. So, the first thing I realize is that no matter what, when we connect the nodes up no node can be left out (the graph needs to be connected). This is because any horse that is not connected to the others means that we don’t have any information about its ordering. Therefore, first, we must run at least 5 races to get some edge for each of the 25 horses. However, this results in 5 disjoint graphs.

We still need to connect these 5 disjoint graphs by picking some horse in each graph for another race (the 6th race). One way is to pick the fastest from each group. In fact, this will give us one of the key information that we need - the fastest horse overall.

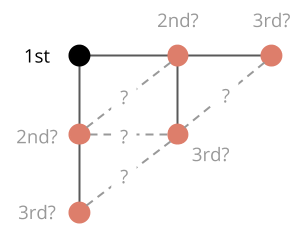

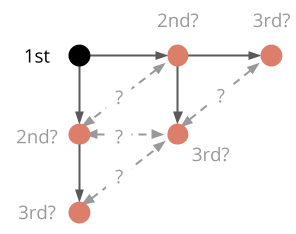

However, we still need to know the second and third fastest. If we look at the current knowledge graph, the fastest horse is connected to two horses. Either of these horses could be the second fastest. Therefore, we need an edge between these two horses in order to know who is faster. We need a 7th race.

What if we didn’t pick the fastest horse to race from each group? For instance, let’s assume we raced the fastest horses from only 4 groups. In that case, we would not know if the horse we left out is the fastest overall unless we had some edge between that horse and the fastest of the other 4 we raced. To have that information, we need at least another race.

In both cases, we proved that there needs to be some number of races 7 or higher (lemma 2). So then, I tried to find a way to solve this with just 7 races.

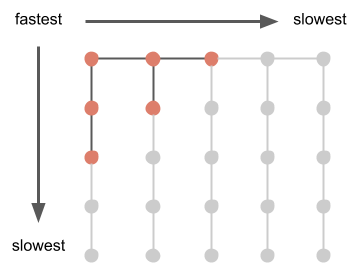

After we raced the horses 6 times, we got this knowledge graph:

We can see that the only horses that could be the second fastest are the ones that are directly connected to the fastest horse. Likewise, we know that the only horses that could be the third fastest are the ones that are directly connected to the contenders for second place.

We are left with 6 horses that are still in the running for first, second, and third. Since we already know which horse is fastest, we just need to race the 5 other horses to find the second and third fastest.

Another race gives us the four edges we need

And there we have it, we found a way to solve the problem with 7 races and proved lemma 1 as well.

Therefore, the minimum number of races needed is 7.

The framework I used in solving this problem can be used to solve many other types of problems:

- Reformulate the problem to remove the cruft

- Define what we need to prove

- Model the problem to break it down and see what we actually need to solve

- Start easy and gradually engineer the solution by:

- Removing the unnecessary parts, and

- Building from the ground up

Remarks

This problem is also recognizable as a topological ordering problem, but I decided not to present it in that way since I wanted to explain it in a more intuitive “knowledge graph” manner.

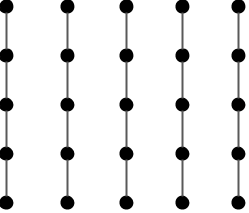

So, I’ll present the topological ordering model here. Let’s take the original “knowledge graph” and make it into a directed graph. For those who are unfamiliar, this just means that each edge points from one node to the other. In this case, we can point from the faster horse to the slower horse for each edge. Going back to the diagrams we had, after the 6th race, the edges would look like:

Here, we can see that a path from horse A to horse B means that we know horse A is faster than horse B. A path is just a way to get from one node to another by only following edges in the direction they point.

The final 6 contending horses would look like:

After the 6th race, we have a path from the fastest horse to any of the contenders for 2nd and 3rd place. The 7th race gives us the path among these contenders (making our directed graph strongly connected).

Comments