My favorite protocol that makes the Internet useful

I remember when I was first dabbling in making online multiplayer video games. I ran into many issues of people “hacking” my game and stealing players’ passwords. Of course, this was a major issue, but I at the time had no clue how these “hackers” could get ahold of the passwords. It was later that I realized that all data sent over the Internet is public. Anyone could see the data that my game’s server sent to the players and vice versa. Whenever a player logged in, their game would send their password to my server for verification. This data was sent over the Internet, and anyone watching would be able to see the password.

So, I had a question.

If anything sent on the Internet could be seen by anyone, how are we able to do anything secure?

How are we able to log in to websites without others seeing our secret information? How are we able to read our emails without others being able to read them as well? How are we able to process financial transactions over the Internet?

At the time I had no clue. I vaguely remember reading some articles about SSL and something about public and private keys, but I didn’t really understand how it all worked. It was not until I took a cryptography course in college that I discovered the protocol behind it all - the Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

To explain this protocol, I’ll present it as a puzzle.

Let’s pretend there’s 3 people - Alice, Bob, and Eve - sitting at a table. Alice and Bob want to agree on something without Eve knowing. Since they are all at the same table, anything Alice communicates to Bob and vice versa, Eve gets to know as well. Each person can also turn their backs to do things in secret, which no-one else can see. How can Alice and Bob achieve this?

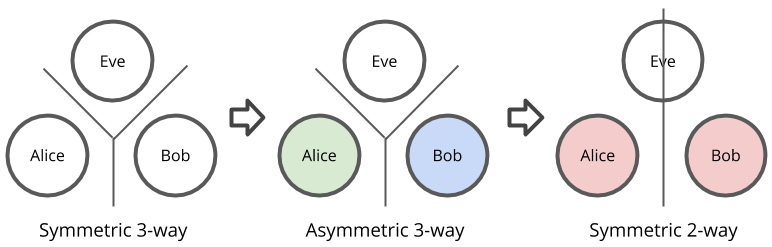

Of course, neither Alice nor Bob would have any prior agreement Eve does not. This means that this is a symmetric system, where all participants are equal in terms of information. However, the goal is to have a protocol that can achieve informational asymmetry.

At first, this might seem impossible. How can Alice and Bob agree on something only they know when Eve can listen in on their whole conversation? Wouldn’t that mean that Eve would always have the same information as Alice and Bob? And thus there’s no way of breaking the information symmetry?

But there is a way. The key is that Alice and Bob can do things in private. The private actions break the overall information symmetry of the system.

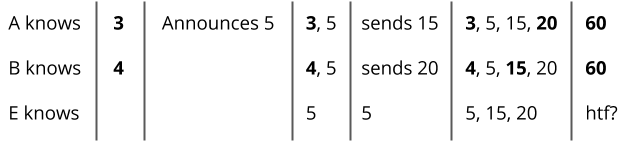

For example, let’s say Alice, Bob, and Eve all start with no information. Then, Alice says “TRIANGLE!” Now, Alice, Bob, and Eve all know triangle. If Bob says “SQUARE!”, then Alice, Bob, and Eve now all know square as well.

This is still information symmetric. But, if Alice secretly thinks to herself “circle…”, then this breaks the information symmetry of the system. Alice now knows something that neither Bob nor Eve knows.

Okay, great. Now we’ve broken the information symmetry. But, this is not enough for what we need though. What we need is that both Alice and Bob share some piece of information that Eve doesn’t have. Therefore, Alice and Bob need to somehow leverage the secret information that they each have to create some secret information that Eve does not have.

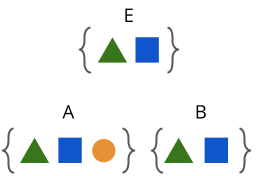

The way we do this is Alice and Bob both choose their own secret number. Alice chooses 3 and Bob chooses 4. Alice then announces some number, say 5, to the table, meaning that everyone knows this number. Then, Bob multiplies his secret number 4 with the 5 that Alice announced to get 20. He then announces 20 back to the table. Alice multiplies her 3 with the public 5 to announce 15. Alice then multiplies her secret 3 with the 20 Bob announced, getting 60. Bob’s secret number was 4, so he multiplies that with the 15 Alice announced and gets 60. And there we have it, both Alice and Bob have the number 60, and Eve does not.

Eve does not know 60 because the numbers that were announced were 5, 15, and 20. No matter how you multiply these numbers, you can’t get 60.

Oh wait.

Eve can actually guess 60 very easily. All she needs to do is divide 15 by 5 to get 3 and 20 by 5 to get 4, and now she can multiply 5 times 3 times 4 to get 60. We’ll need to do something further. Hmm.. how do we make it harder for Eve to guess… How about every time we multiply two numbers, we only take the remainder after it divides by 9.

This time, Alice still announces 5 to start, but instead of sending 20, Bob sends the remainder of 20 divided by 9, which is 2. Alice sends the remainder of 15 divided by 9, which is 6. Bob then multiplies his secret 4 with 6 and divides by 9 to get a remainder of 6. Alice then multiplies her secret 3 with the 2 from Bob to get 6, which, when divided by 9, gets a remainder of 6 as well. Now, Eve has a much harder time finding this common secret (I explain more in Remarks below). Of course, this gets even harder when Alice and Bob use much larger numbers. Try finding what two numbers produce 893498529201 as a remainder when multiplied and divided by 2182841020912383.

Now that I’ve thoroughly confused you with all these numbers, let’s take a step back and see what really happened here. What really happened is that Alice and Bob combined their asymmetries with each other. This process of combining asymmetries produced a symmetry between just Alice and Bob and maintained asymmetry with Eve.

Diffie-Hellman is essentially the same protocol, except that it uses exponentials rather than multiplication and large primes with primitive roots rather than just some small integers. In my example, I used a multiply-divide-get-remainder function, but this protocol works with any function that has these properties:

- The function takes two inputs and produces an output

- The function is commutative and associative, meaning that applying it many times in any order produces the same output

- The inputs are hard to find if given an output

We can see that these properties help us because 1) and 2) help us combine the asymmetries of Alice and Bob, and 3) prevents Eve from doing the same.

To illustrate this protocol in a generic form with an example, let’s say the function is . Alice chooses as her secret and Bob chooses as his secret. The publicly announced value is . Alice announces and Bob announces . Then, Alice gets the secret from and Bob gets the secret from . These are the same value S (because is commutative and associative), which Eve is not able to get. All Eve has is , , and .

So, now that we have such a protocol, how does this enable secure communications over the Internet? Well, the shared information that Alice and Bob create can be a key for encryption. After the protocol, Alice can use the key to encrypt messages she sends to Bob, only send the encrypted message over the Internet, and when Bob receives the encrypted messages, he can use the key to decrypt them and read the original messages. Anyone without this key would not be able to see the contents of the messages. When you are browsing your favorite website, you are essentially going through a similar protocol to generate a key that only you and the website’s servers share. All the communications between you and the website are encrypted with this key. Just make sure the website uses HTTPS and has a valid TLS certificate, but that’s probably for another post.

And there you have it - the protocol that lets you do the useful things on the Internet, like posting to your Facebook wall or ordering that late night delivery from Grubhub.

Remarks

In the example with Alice, Bob, and Eve, why did taking the remainder make it harder for Eve to know what Alice and Bob’s secret numbers were?

Well, first, it’s trivial for Eve to find the secret numbers when the protocol involves just multiplication. Let’s say is the publicly announced number, is Alice’s secret, and is Bob’s secret. Alice sends and Bob sends . Eve can calculate x by just doing , and likewise for . This is because there can only be one that could give and only one that could give .

Now, taking a remainder changes this. Let’s represent taking the remainder after dividing by a number with the symbol . If you were to take any integer , for example, the result can only be one of 3 values - 0, 1, or 2. This means that many ’s could result in a remainder of 0, and likewise for 1 and 2. This is essentially what in cryptography you’d call a hash function, where the function has a large domain but a small range. Of course, just taking the remainder is not a cryptographically secure hash function, but it increases the difficulty by which Eve can find the inputs - the secrets of Alice and Bob. This is because, given a divisor , Alice would send and Bob would send . With just and , Eve would have a harder time finding which and produced those remainders.

Comments